Troy McMullin is an educator who got sidetracked by a small, often inconspicuous organism – lichen. “When I went back to university to obtain a Master’s degree, I wasn’t looking for a career as I already had one as a teacher with a passion for outdoor education, so I decided to focus on something I cared deeply about,” Troy says. His interest in nature and old-growth forests led him to studying lichens. “We know so little about lichens, and yet they’re all around us,” he says. “A tree in my urban front yard uprooted in a storm was home to 30 different lichens.”

As he began to learn about lichens, Troy realized that very few people were studying them seriously in Canada. He spent an extra year researching lichens in other countries and with various specialists and determined there was a clear need for more expertise in this area. Following a PhD and post-doctoral research, Troy was hired as the lichenologist at the Canadian Museum of Nature. While Troy will continue the post’s long-standing academic tradition, he also hopes to make lichens more accessible to the general public. His background in education will be a tremendous asset.

What are Lichens?

Lichens are complex organisms composed of fungus, algae, and sometimes cyanobacteria working together. Lichens can grow almost anywhere as they are self-contained. They can anchor on a rock and pick up minerals and nutrients from the air and water. Over time, they build up space for other species. They grow slowly, however, and don’t compete well with other organisms. Their growth is based on the amount of light they receive while wet, so the amount of rain, fog, and humidity is important. Lichens can be found in deserts, tropical climates, and the Arctic. Many species are restricted to coastal areas. While Garry Oak meadows in coastal BC may appear dry, there are lichens thriving there that cannot tolerate dry conditions thanks to the moisture in the air from being so close to the ocean. In less temperate climates with less consistent moisture, lichens survive by essentially going dormant for extended periods of time.

There are three main forms of lichens:

Foliose lichens have a leafy appearance. They grow on the surface of trees, rocks, or soil and anchor to the substrate but can be peeled off. They can be flat like lettuce or full of lumps and ridges. Lungwort (pictured below) prefers to live in mature forests with humid conditions. Maritime sunburst lichen is a nitrogen-loving species and is commonly found on coastal rocks fertilized by birds.

Fruticose lichens are hair-like and can usually be found hanging down. They have a small anchor but can be detached. Horsehair lichen (pictured below) dangles in twisted hair-like strands from the branches of fir, spruce, and pine in Canada’s boreal forests.

Crustose lichens form a crust on the surface of bark, rock, soil, car, or roof tile and are often brightly coloured. They grow directly into the substrate and can’t be separated. Many of them grow in the Arctic, but they are found throughout Canada. Yellow map lichen (pictured below) is widespread across the country.

Lichens grow profusely in some environments. “They’re very abundant in the boreal forest,” Troy says. “The trees are dripping with it and there can be a half foot-deep lichen mat on the ground.” Lichens are thick in the Arctic as well, making it impossible to walk without stepping on them.

Lichen may appear tough as they can become dormant when conditions aren’t favourable and have evolved to live in difficult places, but they are extremely sensitive. “Lichens are hyper-sensitive,” Troy says. “They get their nutrients from water and air. They’re like sponges and can absorb nutrients easily, but they have no protection. If there’s air or water pollution, they’ll tell you.” If you alter their habitat, even slightly, the lichens will be affected. Draining a wetland beside an old-growth forest will alter the humidity level in the forest and will have an impact on the lichen.

“Lichens are overlooked and understudied, but they tell us so much about the ecological world,” Troy says. You can identify the species of tree or the type of rock by the lichen growing on them. One lichen only grows on iron-rich rock. Hunters in the north use lichen to show them where birds perch, leaving behind nitrogen and a lichen-rich area. “Lichens tell a story and help us understand the ecosystem,” Troy says. “They can show you how light, nutrients, and water flow through habitats.”

Lichens are an important food source for caribou and other boreal forest wildlife, and many insects and arthropods live among lichen. On the prairies, lichens form a biocrust, holding the soil in place and preventing erosion. Cyanobacteria-containing lichens in the Arctic fix nitrogen, passing it on to the surrounding environment. Lichens regulate moisture in the environment by soaking it in and then slowly releasing it. In addition, lichens produce over 1,000 chemicals that aren’t produced anywhere else in the natural world. We have no idea what most of them could do. “We’re in a biodiversity crisis and losing species,” Troy says. “A lot of attention is paid to charismatic megafauna, but the world is run as much if not more so by smaller organisms. Lichens are beautiful, have so many functions, and are an amazing tool for understanding the natural world. It’s tragic not to know what they are when we’re surrounded by them.”

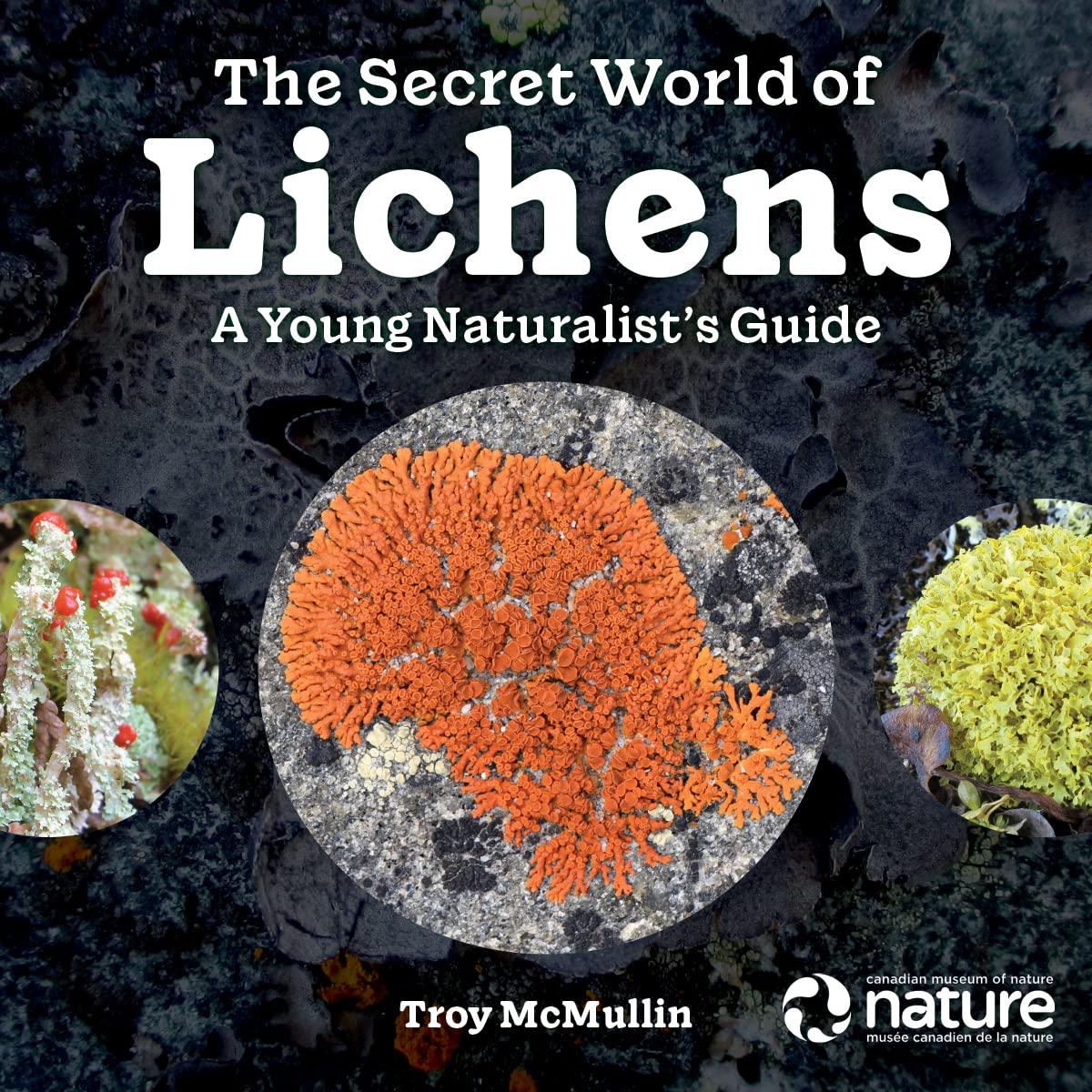

The Secret World of Lichens: A Young Naturalist’s Guide

Identifying lichens is tricky as it requires more advanced techniques. As a result, there are very few guides to lichens. Troy has sought to address this gap by writing a book introducing about 40 of the most interesting and unique species that he has encountered. The Secret World of Lichens: A Young Naturalist’s Guide will be available September 1, 2022, and contains full-page photographs alongside facts and detailed descriptions. While accessible to young people, it will be of interest to curious naturalists of all ages.

Photo credit: Troy McMullin

For More Information

National Lichen Project [Canadian Museum of Nature]

Troy McMullin blog posts [Canadian Museum of Nature]

Lichen Hotspot Discovered on Prince Edward Island, Troy McMullin [Nature Conservancy of Canada]

Discovery Offers New Clues to Lichens’ Evolutionary Advantage [University of Alberta]

Using Metagenomic Techniques to Explore Lichens [EMBL's European Bioinformatics Institute]

EcoFriendly West informs and encourages initiatives that support Western Canada’s natural environment. Like us on Facebook, follow us on Twitter, or subscribe by email.