There are over 32 million kilometres of roads worldwide, subdividing the landscape into smaller and smaller pieces. In the United States, 97% of the land is less than 7 kilometres from a paved road. The Trans-Canada Highway alone takes up 60,400 square kilometres. As Darryl Jones comments in his book, “roads are among the most monumental of all human constructions, yet they are effectively invisible.” Invisible perhaps to humans who take them for granted, but not to wildlife who find their habitat increasingly broken and polluted by roads.

A Clouded Leopard in the Middle of the Road: Thinking about Roads, People, and Wildlife by Darryl Jones outlines the challenges roads create for wildlife as well as solutions being developed worldwide to help birds and animals to safely cross the road. For activists trying to influence roadway additions and upgrades in their community, Jones provides advice and resources.

Roadkill, Barriers & Emissions

A million animals are killed daily on the roads of the United States. Humans don’t emerge unscathed with “around two hundred human deaths, thousands of serious injuries, and over a billion dollars of vehicle damage each year.”

Roads, and the cleared land around them, create a barrier that many animals find difficult if not impossible to cross. Not only are they wary of the fast-moving vehicles and bright lights, they’re also wondering what predators could be waiting in ambush – and the wide, open area ahead offers nowhere for them to hide. Consider the Trans-Canada Highway as it passes through the Bow Valley:

“With an exceptionally broad grassy median and similarly expansive verges on either side, the entire road corridor is relatively wide, especially for what is mainly just four lanes of traffic. In places, the distance between the forest edges at either side of the road is up to ninety meters (one hundred yards) across; that’s a very long way for any animal wanting to cross, let alone a tiny bird not used to flying any distance.”

You might imagine that birds wouldn’t be affected, but that isn’t the case. A recent Australian study found that “the wider the road, the less likely birds were to cross, and that the small forest-dwelling species were the most reluctant to cross any road of any size.”

Roads generate dust, fumes, vibrations, and noise. Traffic noise interferes with wildlife communications, including mating calls, and may mask the sound of approaching predators. Some animals, such as Australia’s kangaroo rats drum the ground with their large feet to communicate, but traffic noise makes this impossible.

Less research has been done into the impact of vehicle emissions although it is known that the fumes from unleaded gasoline have a serious impact on insects. The absence of insects “accounts for the almost complete absence of insectivorous bats in the night sky above, or even near, almost any road anywhere in the world.”

Jones describes roadside habitats as population sinks: “places that attract a regular influx of individuals because of the constant availability of new living spaces – spaces vacated as a result of seemingly endless unfortunate accidents. The animals that settle in these risky districts are often the young, inexperienced, or desperate, those with no other options.”

Road Crossings

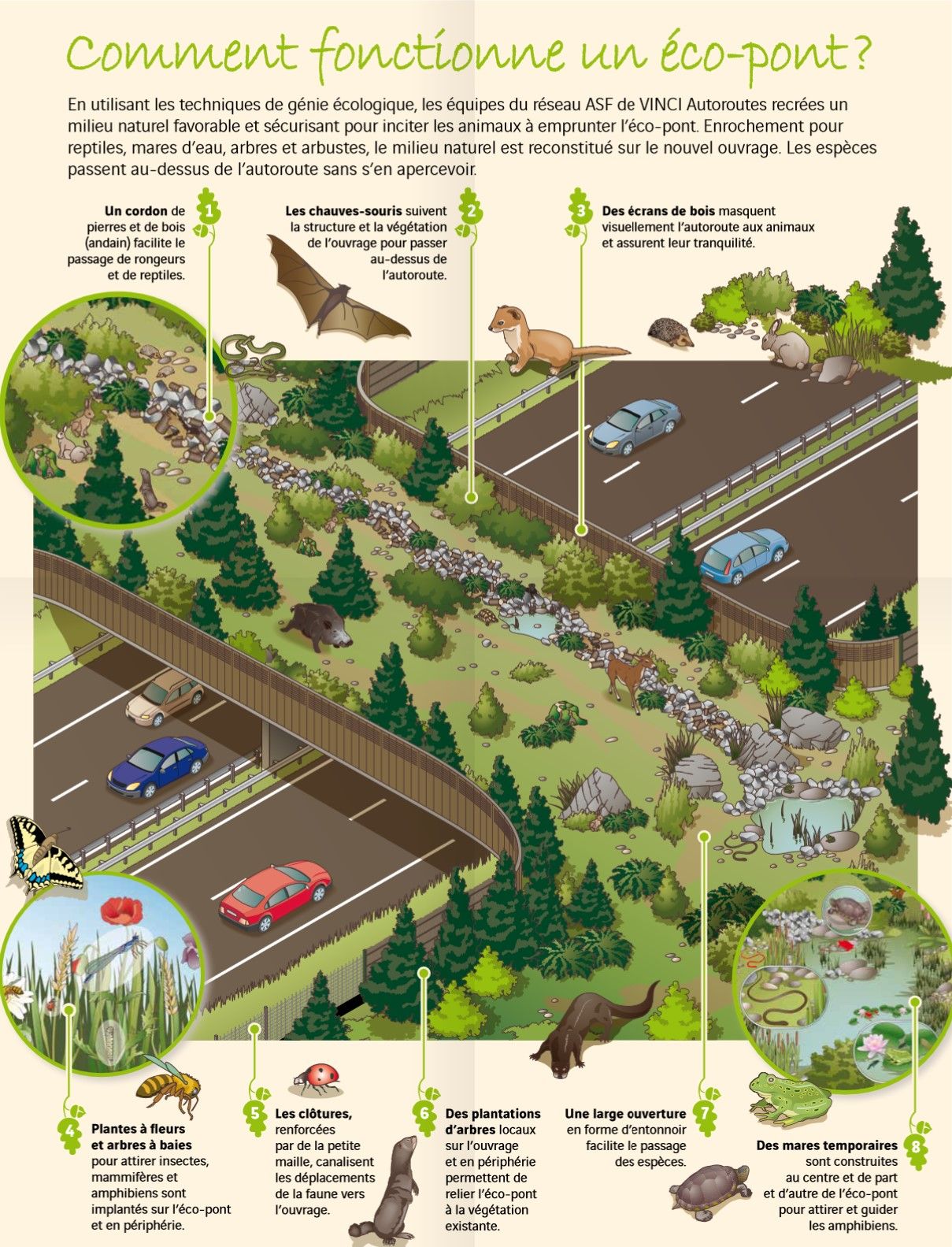

Europe leads the way in constructing wildlife road crossings. Installation of small culverts to protect migrating amphibians began in the 1950s; there are now thousands. France built the first overpass in 1963; it now has a crossing structure roughly every eight kilometres.

The Trans-Canada Highway as it passes through the Bow Valley has also shown leadership. The first crossing structure was installed in 1983. By late 2020, there were 45 underpasses and 7 overpasses.

Both overpasses and underpasses have evolved over time. Australia’s Karawatha Forest Overpass incorporates viaducts, rope ladders, fauna underpasses, and vegetation. Some road crossings have been developed to meet very specific wildlife needs, such as dormouse bridges in the UK and glider poles in Australia for gliders and possums.

Rather than focusing on one bad spot for roadkill or one new roadway upgrade, road ecologists are adopting a broader perspective: “Taking in an entire catchment or valley, the flow of the water bodies, and the geography of the forested remnants – has allowed fresh insights into how animals might be able to move through the wider area and how a road might be routed to avoid sensitive locations.” Through a combination of tunnels and viaducts, the C37 highway in northern Spain has no inclines or slopes. “Almost half (48 percent) of the entire road is under or over the land. In other words, wildlife can move unimpeded across about half the route of this major motorway, in most places without even being aware that it is there.”

Collaboration

Local environmentalists are well aware of the challenges involved in getting road designers and builders to take ecological perspectives seriously. Jones goes into considerable detail about cases where environmentalists and road construction specialists have collaborated successfully. He emphasizes the importance (as outlined in The Rauischholzhausen Agenda for Road Ecology) of focusing on practical issues of road planning and construction and providing evidence-based arguments to support wildlife crossings.

Additional Resources

A Clouded Leopard in the Middle of the Road: Thinking about Roads, People, and Wildlife, Darryl Jones (2022)

Handbook of Road Ecology, Rodney van der Ree, Daniel J. Smith, Clara Grilo (2015)

The Rauischholzhausen Agenda for Road Ecology, I. A. Roedenbeck et al. (2007)

Safer, more permeable roads: Learning from the European approach, Darryl Jones (2010)

Jasper National Park has almost 4 times the roadkill compared to Banff: Here’s why, CBC

Unusual Bridges for Animals: Wildlife Overpasses, The World Geography (photographs)

Photo credit: https://www.flickr.com/photos/apmckinlay/15936285323, diagram - https://patrimoines.ain.fr/data/illustration_ecopont_vinci.pdf

EcoFriendly West informs and encourages initiatives that support Western Canada’s natural environment through its online publication and the Nature Companion website/app. Like us on Facebook, follow us on Twitter, or subscribe by email.